C. G. Jung

Cartea Roşie

Editată de Sonu Shamdasani

Traducere de Viorica Nişcov şi Simona Reghintovschi

Editura Trei, 2011, 404 p.

Deși editorul său, Sonu Shamdasani, considera că sînt de prisos comentariile asupra unui astfel de document cultural, care spune prin el însuși tot ceea ce este de spus, cercetările care apar în Occident îl contrazic, acestea nefiind doar numeroase, ci și foarte consistente, provenind din diverse zone teoretice: psihanaliza jungiană, știința religiilor, istoria ideilor, antropologie, istorii de viață și memorialistică, studiul imaginii etc. Cercetarea mea aparține filonului „istoriilor de viață“.

Legendele și miturile personale fascinează prin aceea că oferă, oricui vrea să înţeleagă, un răspuns la chestiunea Sinelui şi ne conduc spre tema principală a unei vieţi: „Eu eram suma emoţiilor mele şi un Altul în mine era piatra atemporală, nepieritoare“, spune Jung înAmintiri, vise, reflecţii şi viaţa lui se organizează – timp de 16 ani – în jurul nevoii de a răspunde la întrebarea cine era acest Altul și de a reconstrui figurile multiple ale acestui Altul.

Pentru a-şi lămuri marea frămîntare, Jung coboară adînc în hăţişul inconştientului, se confruntă cu propriul Infern, intră în haosul unui suflet tulburat şi indecis, îşi explorează dezorientările şi caută aici, în adîncul din el, un sens al propriei vieţi. În acelaşi timp însă, el coboară departe, în istorie, pînă la culturile antice, se orientează apoi spre spații îndepărtate, India și Extremul Orient, se interesează de gnostici – autori ai unei mistici a Sinelui – și de gnoza timpului său, redeschizînd aceste filoane de gîndire, cu o imensă vigoare, prin autobiografia spirituală, intitulată Cartea Roşie. Acest impresionant document cultural descrie experiența cu caracter mistic a autorului său, relația lui absolut personală cu planul divin, cu figura christică, cu Dumnezeul său personal și cu diverse alte zeități, cu diavolul etc., toate aceste întîlniri fiind semnul anumitor stadii ale împlinirii. Avem în fața ochilor episoade ale unei vieți, mai precis, ale unei vieți în profundă criză, ce construiesc „mitul personal“ al autoruluiCărții Roșii, al peregrinului care o ia pe calea Sinelui.

Ce află Jung parcurgînd această cale? Ce ghizi spirituali îl însoţesc în marea călătorie? Care este chemarea lui Jung şi marea operă pe care trebuie s-o înfăptuiască? Care este secretul lui Dumnezeu? Cine sînt apropiaţii care-i împărtăşesc tulburările şi care-l însoţesc pe drumul Sinelui? Toate acestea sînt cîteva întrebări la care răspunde impresionantul document cultural „iluminat“ (după expresia mai multor exegeți) care este Cartea Roșie.

Sufletul nostru, o figură multiplă cu care se poate dialoga

Iată cel mai semnificativ lucru pe care l-a descoperit Jung parcurgînd calea Sinelui: „Cine nu cade în stăpînirea oamenilor, cade în mîinile Zeului. Ferice de El şi Vai de El“ (Cartea Roşie, p. 341). Dar în stăpînirea cui sîntem noi? Aceasta, probabil, va deveni o chestiune capabilă să genereze baza unei interogaţii absolut personale pentru toţi cei care sînt interesați de parcursul cultural și de viața atît de specială a unui mare gînditor și inițiat al umanității.

Cartea Roşie – autobiografia spirituală şi receptaculul operei lui Jung – ar trebui citită aşa cum se cuvine unei astfel de opere: cu multă răbdare şi atenţie, cu o stare pe care aş numi-o asceză. Numai aşa se poate înţelege că oamenii care „cad în mîinile Zeului“ sînt visătorii, vizionarii, cei care ajung la „protomateria“ ce se zbate în interiorul lor. Unii o fac cu intenţia de a realiza o muncă originală, alţii, fără nici un fel de intenţie creatoare (deci, fără nici un raport cu condiţia geniului), ci pur şi simplu pentru că nu au încotro, pentru că destinul îi forţează: „Trebuie să mergi pe drumul tău, nepăsător faţă de ceilalţi, fie că sînt buni, fie că sînt răi... Ţi-ai pus mîna pe divinitatea pe care aceia nu o au“ (Jung, „Încercări“, Cartea Roşie).

Cartea Roşie este o veritabilă interlocuţiune: ea implică un narator care, în cazul de faţă, este atît autorul propriei legende și născătorul propriului Sine, cît şi iniţiatorul unei anchete, al unei serii de interviuri cu personaje dintr-o altă lume, numită de Jung „cealaltă realitate“, avînd rolul de călăuze sau ghizi spirituali. În acest parcurs, personajele intervievate – fragmente ale sufletului autorului – sînt fizicalizate, îşi cîştigă dreptul la realitate, sînt efectiv percepute pentru că sînt „fantasme vii“ înregistrate prin modalităţi senzoriale diverse (vizuale – imaginile personajelor sînt foarte bine definite formal şi cromatic, de exemplu diavolul este Călăreţul Roşu, primeşte chiar numele Roşul, Moartea primeşte numele Întunecatul, este un personaj purtînd haină neagră, în falduri, un bărbat stînd nemişcat şi privind în depărtare, slab şi palid, care spune despre el: „inimă nicicînd nu am avut“ (p. 274); termice – Întunecatul este rece, Roşul este cald, e flacără, e sînge; auditive – sufletul vorbeşte uneori cu voce de femeie şi-i spune că ceea ce face e „artă“, alteori sufletul îi vorbeşte cu voce bărbătească şi-i spune care este chemarea lui: „noua religie şi proclamarea ei“; este de menţionat că primele reprezentări senzoriale ale fantasmelor sînt, de fapt, auditive, apar încă din copilărie şi se referă la discriminarea în interior a unei voci, alta decît a lui, o arrhevoce aparţinînd unei personalităţi atemporale, Personalitatea 2, cum este numită în cartea de amintiri).

Cartea Roșie, un model de construcție spirituală

Interlocuţiunea despre care vorbeam are un rod foarte special, şi anume, Sinele. Dar cine este Sinele? Nimeni altul decît copilul divin, christosul personal. Istoria de viaţă a lui Jung este o transfigurare, este aducerea la o nouă realitate a legendei Sfîntului Cristofor. Uriaşul care-şi poartă cu greu povara enormă – un copil, pe pruncul Iisus – este un simbol nesatisfăcător pentru Jung, prin urmare, el va fi reconfigurat și va deveni copilul fragil, care poartă pe umeri un uriaş, iar acest uriaş îi pare o povară uşoară. Transformarea are la bază chiar cuvintele lui Christos: „Căci jugul meu e bun şi povara mea este uşoară“ (Evanghelia lui Matei, citată în Cartea Roșie, p. 282). Jung face din Cartea Roșie și, mai tîrziu, din Răspuns lui Iov un veritabil laborator de transformare a simbolurilor gnostice.

Autobiografia spirituală a lui Jung este interesantă atît pentru calitatea acesteia de „model“ (nu se poate nega importanţa ei în formarea spirituală), cît şi pentru că pune la dispoziţia cercetătorului o bază empirică alcătuită dintr-o „protomaterie“ impresionantă. Din acest punct de vedere, nu cred că este exagerată afirmaţia că demersul lui Jung este unic, în sensul că poate stimula dezvoltarea cercetării în antropologie, dar şi în alte ramuri ale ştiinţelor umane, pe direcţii cu totul noi, deoarece, pînă în acest moment, opera lui Jung a constituit, în principal, o bază pentru aplicarea şi rafinarea procedurilor terapeutice în cabinetele de specialitate. Au fost mai puţin explorate alte dimensiuni ale impresionantei sale producţii culturale ce pot furniza, de exemplu, instrumente pentru analiza operelor culturale, absolut indispensabile în activitatea criticului şi a teoreticianului culturii, sau proceduri de identificare a structurilor inconştiente pe fundamentul cărora se înalţă ariile culturale, ori de discriminare – pe fondul diferenţelor culturale – a arhetipurilor comune ce ne îndreptăţesc să vorbim despre producţii cu valoare universală, toate acestea fiind indispensabile în activitatea antropologului.

Simt nevoia să fac nişte precizări în legătură cu calitatea de model al autobiografiei spirituale a lui Carl Gustav Jung, deoarece unora ar putea să li se pară forţată această idee, cu atît mai mult cu cît autorul pare să excludă propria ipostază de formator al spiritului, „Ceea ce vă dau nu este teorie şi nici învăţătură“ sau „calea mea nu este calea voastră“, spune el în Cartea Roşie (p. 231). Dar parcursul prin care ia naştere copilul divin, Sinele lui, este un model prin metoda pe care o urmează, prin drumul interiorităţii pe care se angajează naratorul. Aşadar, dacă descrierea acestui parcurs personal ne conduce la desluşirea procesului care a generat-o şi a susţinut-o, „calea adîncului“ are, implicit, calitatea de model, nu ezit să spun a unui model de urmat, repet, în procesualitatea lui şi nu în reproducerea conţinuturilor sale – lucru care, de altfel, este şi puţin probabil, şi inutil. Cartea Roşie poate fi, deci, un model în ceea ce priveşte tehnica intervievării fragmentelor de suflet, a personajelor noastre interioare.

Deşi, după cum consemnează biografa Deirdre Bair în Jung. O biografie (p. 247), metoda lui „neortodoxă“ şi destul de „înspăimîntătoare“ l-a pus pe gînduri. Jung a putut constata în mod direct sau observîndu-i pe pacienţii care urmau aceeaşi cale că e o metodă ce poate conduce la „vindecarea de sine“ sau la integrarea Sinelui. În mare, metoda constă în producerea de viziuni, după cum descrie una dintre pacientele lui Jung: „Mai întîi foloseşti doar retina ochiului pentru a obiectiva. Apoi, în loc să continui să încerci să forţezi imaginea să iasă afară, trebuie doar să vrei să priveşti înăuntru. Acum, cînd vezi aceste imagini, vrei să le reţii şi să vezi unde te duc – cum se schimbă. Şi vrei să încerci să intri în imagine tu însăţi – să devii unul dintre actori“, citată de Sonu Shamdasani, editorulCărţii roşii (p. 216), pentru a semnala faptul că Jung îi familiariza pe pacienţi cu propriile lui tehnici de imaginaţie activă şi îi învăţa să le urmeze pentru a stimula fluxul de imagini şi pentru a-şi scrie propriile cărţi roşii.

Pledoaria lui Jung pentru conştientizarea procesului de individuaţie şi pentru naşterea formaţiunii Sinelui (omul complet, al cărui simbol este copilul divin) transformă automat calea pe care el a urmat-o, calea Sinelui – descrisă în Cartea Roşie –, în model: „Diferenţa între procesul de individuaţie natural, care se desfăşoară în inconştient, şi cel conştientizat este uriaşă. În primul caz, conştiinţa nu intervine nicăieri; prin urmare, sfîrşitul rămîne la fel de obscur ca începutul. În cazul al doilea, dimpotrivă, iese atît de multă obscuritate la lumină încît, pe de o parte, întreaga personalitate este iluminată, iar pe de altă parte, conştientul cîştigă în amploare şi înţelegere“, spune Jung. Procesul de individuaţie este lucrarea divină din om. Atunci cînd este adusă la lumina conştiinţei prin efort personal, prin asumarea drumului interior şi nu prin supunerea la dogmă sau executarea automată a ritualurilor specifice diferitelor religii, imaginea lui Dumnezeu se realizează în formaţiunea Sinelui. Dumnezeu şi omul coincid în arhetipul Sinelui, iar această idee susţinută în conferinţe şi publicată este bazată pe calea asumată de Jung: „Căutaţi drumul prin exteriorităţi, citiţi cărţi şi ascultaţi păreri: la ce bun? Există o singură cale şi asta e calea voastră... Să meargă fiecare pe calea lui“ (Cartea Roșie, p. 231).

Fragment din lucrarea O istorie de viață excepțională: Carl Gustav Jung de

Lavinia BÂRLOGEANU

Béatrice

Un ouvrage qui vous happe.

En tant qu'objet : sa taille, la qualité de son papier, sa qualité esthétique (enluminures et oeuvres picturales)vous saisissent.

Vous y découvrez la profondeur créatrice de Jung. Il ne traite, dans cet ouvrage, ni de sa vie, ni de son approche. Il crée... Et vous vous imprégnez de ce qu'il crée.

La beauté de ce qu'il peint, la poésie mythique de ce qu'il écrit, manifestent une puissance inouïe, une vibration étonnante.

La lecture de cet ouvrage vous fait basculer dans un monde propre à l'auteur, et pourtant fortement en résonance, sans doute, avec chacun... un chemin vers le Soi...

Jung n'est pas ici, de prime abord, spectateur du monde extérieur (patient ou société), mais explorateur de son monde intérieur.

Rencontre de l'Orient et de l'Occident, de la lumière et des ténèbres. Action de l'une sur l'autre...

Parcours initiatique...

Epiphanie de la lumière...

Par-delà le bien et le mal...

Sans doute les mystiques de toutes religions retrouveront-ils dans ce livre des expériences connues, de même que tout homme en quête de lui-même... qui retourne peu à peu vers le Tout...

Et l'on pense à Rimbaud et aux étapes narrées dans "Une Saison en enfer"...

Après avoir écrit une oeuvre poétique singulière, Rimbaud a délaissé la littérature pour parcourir le monde

Après avoir écrit le "Livre rouge", Jung a bâti une maison singulière.

Un livre magnifique, qui vous envoûte et vous recharge, qui vous nourrit intérieurement. Une source à laquelle il ne nuit pas de s'abreuver aujourd'hui.

Et l'on se prend à rêver de voir cet ouvrage joué sur une scène, au moins par extraits...

Aus dem Dschungel des Unbewussten.

Von Theodor Itten

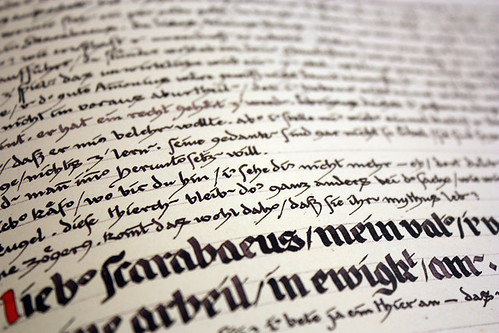

Es begann am 12. Dezember 1913, in C.G Jungs Studierzimmer im stattlichen Haus an der Seestrasse in Küsnacht, Schweiz. Das psychologisch wissenschaftliche Experiment seiner Konfrontation mit dem Unbewussten nahm Jung in seinen Bann. In seinen Lebensaufzeichnungen Erinnerungen, Träume, Gedanken (1961) sagte er rückblickend, es war ein Experiment, das mit mir angestellt wurde. Hier wurzelt sein psychotherapeutisches Lebensmotto: "Wir leben und werden gelebt". Hauptsache: nie gegen das Unbewusste. In dieser Adventszeit setzte sich der Arzt, Psychiater und Pfarrsohn (1875-1961), an sein Schreibtisch,"...dann ließ ich mich fallen". Was daraus geworden ist, können wir nun in diesen intimen und privaten Aufzeichnungen lesen und anschauen. Wir nehmen teil an Carl Gustav Jungs Untersuchungen der Prozesse des kollektiven Unbewussten. Es handelt sich hier um eine umfangreich verspielte Phänomenologie, jenseits der damaligen akademischen Psychologie. Jungs eigene im Entstehen begriffene Psychologie beschäftigt sich mit inneren Vorgängen, in Form von Träumen, Imaginationen, Visionen und zweite Gesichter, welche sich auf dem reichhaltigen Gebiet der menschlichen Erfahrung machen lassen. Diese inneren Erfahrungen waren für ihn Quell des Individuationsprozesses der Seele. Ich bedacht nicht, dass meine Seele nicht der Gegenstand meines Urteilens und Wissens sein kann; vielmehr ist mein Urteilen und Wissen Gegenstand meiner Seele. Als Arzt und Seelenheilkünstler machte Jung sich zum Meister und Diener der Seele und ihrer Wandlung in seinem Selbst. Die Bilder und Imaginationen die er im Roten Buch aufgeschrieben hatte, oft in einer Sprache die an Augustinus und Nietzsche erinnert, bezeichnete er später, nachdem er ab 1928 den Alchemisten und dem Geheimnis der Goldenen Blüte Chinas begegnet war, als 'Das Kollektive Unbewusste' und seine Archetypen. Der 38 jährige Familienvater schrieb und zeichnete von nun an jeden Abend seine imaginären Dialoge, Traumwanderungen, Bilder und Gedanken in gesamthaft sechs, in schwarzes Leder gebundene Notizbücher auf. Das nun vorgelegte 'Rote Buch', ein in rotes Leder gebundener Folioband, enthält, wie Aniela Jaffé, Mitherausgeberin der Jung Biographie bemerkte, "...die gleichen Phantasien in ausgearbeiteter Form und Sprache und in kaligraphischer gotischer Schrift, nach Art der mittelalterlichen Handschriften." Das Rote Buch ist in zwei Abschnitten gegliedert. Liber Primus mit 11 Kapiteln und liber Secundus mit 21 Kapiteln. Liber Primus beginnt mit dem Weg des Kommenden und macht in der Wiederfindung der Seele, seinen ersten Halt. Es folgt Seele und Gott, Gedanken über den Dienst der Seele, die Wüste und Erfahrungen in der Seele sowie die eigene Höllenfahrt in die Zukunft. Weiter geht es mit der Zerspaltung des Geistes, dem Heldenmord, und Gottes Empfängnis. Das Mysterium: Begegnung, Belehrung, Lösung, beendet diesen ersten Teil. Liber Secundus öffnet mit den Bildern der Irrenden. Der Rote, hat seinen Auftritt und führt zum Schloss im Walde. Einer der Niedrigen folgt, der Anachoret zeigt sich in all seiner Pracht. Der Tod führt die Wanderschaft über die Reste früher Tempel. Erster Tag. Zweiter Tag. Die Inkantationen, leiten über zur Eröffnung des Eies. Die Hölle wird besucht, der Opfermord erzählt. Die göttliche Narrheit gefolgt von Nox secunda bis quarta. Die letzten Kapitel über die drei Prophezeiungen, die Gabe der Magie, der Weg des Kreuzes und der Zauberer, überfüllen die Schale des Urstoffes für Jungs Lebenswerk. Die Prüfungen schließen mit seinem Nachtrag im Herbst 1959."Ich habe an diesem Buch 16 Jahre gearbeitet. Die Bekanntschaft mit der Alchemie 1930 hat mich davon weggenommen.Da fand der Inhalt dieses Buches den Weg in die Wirklichkeit. Ich konnte nicht mehr daran arbeiten."

Das Rote Buch in Faksimile ist auf 180 Seiten ein Genuss, obschon die Schrift gewöhnungsbedürftig ist. Jungs Zeichnungen sind schön. Seine Träume sind die leitenden Wellen seiner Seele. Eine Kostprobe: Der Geist der Tiefe hat allen Stolz und allen Hochmut der Urteilskraft unterworfen. ER nahm den Glauben an die Wissenschaft von mir, raubte mir die Freude des Erklärens und Einordnens, und er ließ die Hingabe an die Ideale dieser Zeit in mir erlöschen. Er zwang mich hinunter zu den letzten und einfachen Dingen. Die Wüste und Klöster in uns. Das Eine habe ich gelernt, dass man nämlich dieses Leben leben muss. Dieses Leben ist der Weg, der längst gesuchte Weg zum Unfassbaren, das wir göttlich nennen. Es gibt keinen anderen Weg. Alle anderen Wege sind Irrpfade. Das Experiment der aktiven Imagination mit sich und in sich selber, ist eine gewagte Technik um den inneren Vorgängen auf den Grund zu kommen. Die Frage ist: Soll so ein unvollendetes, intim privates Buch überhaupt veröffentlicht werden? C.G. Jung zögerte zu Recht, denn er hat ein Anrecht auf den Schutz seines "interio intimo meo". Sein einziger Sohn Franz (1908-1997) würdigte Vaters Testament von 1958, wo dieser seinen Wunsch aussprach, das Rote Buch möchte bei seiner Familie verbleiben. Die famosen wortreichen Destillate finden sich in Jungs zahlreichen Bücher ab 1928, welche dieser großartige Wissenschaftler der eigenen Seele, uns zugeeignet hat. Frühere kurze Teilveröffentlichungen von Auszügen aus dem Roten Buch, wie die in seiner Autobiographie, fand er in Ordnung. Leider entschieden die Enkel Jungs, auf Drängen eines Psychologiehistorikers, S. Shamdasani, dass das Rote Buch publiziert werden dürfe. In seien Einleitungsworten schlägt dieser, der in früheren schlanken Publikationen auf renommierte C.G. Jung Forscherinnen und Forscher schimpfte, sie mit seiner giftigen Feder verschmähte, selbstbezogene dogmatische Töne an.

Diese Publikation ist nicht die alles Entscheidende, wie der Redaktor es uns gerne glaubhaft machen möchte. Es ist kein Neuanfang, den machte Jung selber vor 80 Jahren. Wir brauchen die Geschichte der jungianischen Psychotherapie und Jungs Biographie nicht umzuschreiben. Hier besteht keine Notwendigkeit für ein 'entweder/oder' ' 'dafür oder dagegen' sein. Die Publikation des Roten Buches ist ein 'und'' Für viele leidenschaftliche Jungianerinnen und Jungianer eine willkommene Ergänzung ihrer Bibliothek. Bekannte C.G. Jung Wissenschaftler und Biographinnen, wie James Hillman, Deirdre Bair und Andrew Samuels, denen das Werk und Leben Jungs wichtig ist, kommen zu anderen Einsichten und Erkenntnissen. Wie viel beflügelnder und seelenwahrhaftiger wäre es doch gewesen, die Enkel hätten Großvater sprechen lassen. In seinem Kapitel Auseinandersetzungen mit dem Unbewussten in der Autobiographie, hat er die beste Einleitung niedergeschrieben. Manchmal ist es wertvoller auf den sich in den Seelentiefen auskennenden Großvater zu hören, als einem, sich mit so einer unnötigen Publikation selbst wichtigmachenden Historiker, auf den Leim zu gehen. C.G. Jung findet nämlich ein Dogma "... ein indiskutables Bekenntnis das nur dort aufgestellt wird, wo man Zweifel ein für alle Mal unterdrücken will. Das hat mit wissenschaftlichem Urteil nichts mehr zu tun, sondern nur noch mit persönlichem Machtrieb." Die Privatsphäre von C.G. Jung selig, fasziniert enorm. Trotzdem, müssen wir nicht alles wissen, sondern brauchen vor allem unsere eigenen tiefenpsychologischen Erfahrungsschätze.

Theodor Itten

Ein Geschenk vom "Geist der Tiefe"

Von Michael H

Format:Gebundene Ausgabe

Als junger Mensch lernte ich das katathyme Bilderleben kennen und machte weite Reisen in das Unbewusste. Heute nach 30 Jahren und der Lektüre des roten Buches weiß ich endlich, das die dort besuchten Orte kein Produkt meiner Phantasie waren, sondern '"objektive"', sozusagen reale Orte. Wie hätte Jung ansonsten (in vielen Teilen) genau das gleiche schauen können.

Seine Interpretation davon bleiben seine eigenen. Ich kann sie nur zu einem Teil nachempfinden. Aber das Gefühl "mein Sein" bestätigt zu finden ist überwältigend.

Wie hier auch von dem Rezensenten Herrn Itten, wird die Veröffentlichung von Jungs '"geheimen' Tagebuch" oft angegriffen. Dabei richtet es sich in jedem Satz direkt an den Leser. Ein 'Tagebuch' sieht ganz anders aus.

Als Jung sich gegen eine Veröffentlichung wehrte, kannte er sehr wohl 'den Geist der Zeit', der ihn und sein Buch vielleicht zerrissen hätte. Dieser Geist hat sich gewandelt und wenn er heute auch nicht weniger zwingend ist als zu Jungs Zeiten, so erlaubt er doch die Veröffentlichung dieses Buches. Das beweist die breite und wohlwollende Annahme die es erfahren hat.

Es ist sehr richtig zu sagen 'wir brauchen unsere eigenen tiefenpsychologischen Erfahrungsschätze', aber wir brauchen auch etwas wie dieses rote Buch, das uns hilft diese Erfahrungen annehmen zu können, die Bedeutung dieser Erfahrungen zu erkennen und echten Nutzen daraus zu ziehen. Dabei hilft uns die heutige, akademische Psychologie wahrlich nicht. Jungs 'Geiste der Tiefe' steht sie immer noch hilflos psychologisierend und ins Individuelle verweisend gegenüber.

Ich danke allen, die diese Veröffentlichung möglich gemacht haben, von ganzem Herzen. Und wenn sie damit viel Geld verdient haben und sich ordentlich 'wichtig gemacht' haben, es sei ihnen gegönnt. Für mich ist dieses Buch ein großes Geschenk.

Vielleicht sollte man den potenziellen Käufer auch vor falschen Erwartungen warnen. Dieses Buch erklärt nichts, sondern es zeigt auf. Es verlangt, gerade von unerfahreneren Lesern, eine enorme Bereitschaft sich einfach einzulassen auf die tiefste innere Welt eines Menschen. Einer Welt, von der die Meisten wohl noch gar nicht wissen dass sie existiert. Ein kleines Stück begleiten wir Jung dabei sich diese Welt zu erschließen, seine Führung in ihr zu finden. Ob wir dabei irgendetwas Bereicherndes erfahren, liegt ganz an uns selbst.

Seine Interpretationen dazu sind geprägt durch sein enormes Wissen über Mythen, Religionen und klassische Philosophie. Oft genug habe ich darum beim Lesen nicht mehr folgen können, blieb mir das was er vermitteln wollte im Halbdunkel. Ein gebildeterer Leser hat es da sicher leichter.

Journey to the centre of [a] man

By Peter FYFE

If you are of sound mind, stout heart, and good character, join CG Jung on the most intrepid and exhilarating journey imaginable: the journey to the centre of [a] man (that is if you can pry this book from the cloying grip of the academics and fundamentalists long enough to enjoy it for what it is and have the grace to let it be just that).

Be warned: it's tough going. You'll be exposed to primordial figures that may remind you of some of your own. You'll be thrown into a bewildering desert of early-twentieth century Swiss-protestant metaphysics (heavily spiced by Goethe, Nietzsche, and assorted mythologies). You'll see some of the complexes and neuroses of a great man exposed in all their horror and occasional hilarity. You'll marvel as big ideas find their first voice in a seemingly unwilling recipient. You may even share a little of the horror and pain as Jung fails to see the joke his own psyche is playing on him, or perhaps even occasionally misses the point? Best, you'll see many symbols and wonders of the soul that, whilst being all too familiar, remain elusive, beckoning, and truly awesome to behold. Yep, it's your basic esoteric hero's journey, writ large, for all to misinterpret.

The Red Book is a beautiful, rare, and unique artefact of someone else's process. It's almost like a travel book, documenting CG's personal and idiosyncratic journey across the great undiscovered country within. Like its author, it's a book that will draw out and amplify each reader's deep psychological prejudices (you may have already glimpsed some of mine). And it reveals that author and his psychology in a way his [or anyone else's] more conventional works never have.

If you love exploring the human soul, I'd be surprised if you didn't find this the most fascinating, exasperating and incredible book you've ever read, as I have. Enjoy, but be warned: you may loose some sleep over it!

PS: As befits the subject, the standard of scholarship and presentation of this book is exhaustive, exhausting, and without parallel.

A very intimate insight into Jung and his psychology

By Mr. G. M. Rose

In future years Jung's character will be micro-analysed on the basis of what he has set down in these words; his enemies will point to the text to show how clearly pathological he was, and his admirers will quote from this book to show exactly how enlightened and ahead of his time he was.

I have found Jung's 'The Red Book' fantastical, grandiose, poetic, spiritual, and inspirational. Whatever perspective/s you take on the text, one thing is for certain 'The Red Book' provides the reader with the most intimate insight into Jung's internal world and his creative engagement with that world yet published. Moreover it is the 'prima materia' for his approach to psyche and laid the foundations for his entire pschological theory.

For these reasons the 'The Red Book' is a fantastic work and an essential read for anyone with any interest in Jung and/or his psychological perspectives.

deeply fascinating and inspiring

By Lars

How can i possibly review this book, was my first thought, and it still is. I decided to do so anyway, because i think it might bring something to the table.

The book is huge, the imagery alone would take a tremendous amount of time to study. These things contribute to a certain "wow" effect that needs to settle before one begins reading the actual text, or, well at least in my case, even think of doing a review of the book.

So here we are: The book itself. The first's part of the book contains a preface by Ulrich Hoerni Followed by Jung's artwork and calligraphy presented as an original re production of Liber Novus. At the back of the book is the translation, which I think is very well done, I should say I do read German, but I'm in no way a professional translator. The book is devided into liber primus and liber secundus and scrutines which contain an entry of black book 5 (bare with me but I'm gonna quote Sonu Shamdasani from a Harpers magazine article instead of explaining the black books myself:

"To begin with, one must clearly differentiate Jung's Black Books, in which he initially wrote his fantasies together with reflections on his mental states, from Liber Novus. The former were records of a self-experiment, while the latter drew in part on these materials to compose a literary and pictorial work."

So is there a "before and after the red book" which has been state before. I cant say, I don't think anyone can for sure. After reading the book I had a lot of AHA! moments contributing to a better understanding of some of Jung's other works. The book has given me a much much clearer image of Jung as a person, but that image is inheritably flawed, simply because I did not know Jung. So weather or not the book, takes away from Jung's image, or adds to it, is in the end, not really that interesting.

The book is more straightforward in its text then many of Jung's academic works and as such is easier to read. The concept though, is far from straightforward and might take a lot longer to absorb then the usual academic material from Jung.

Extraordinary

By B. Hill

In 1913, a 40 year old world renowned psychologist suffers recurring dreams and visions of world catastrophe. His expertise as a psychiatrist working with incurable psychotics forces him to conclude that he is on a course to madness. His training as a scientist compels him to meticulously document what he imagines will be his unavoidable decline into insanity. With the outbreak of World War I, he experiences relief in the realization that the images that have haunted him over the prior ten months pictured not his own undoing, but that of the world. As the outer conflict unfolds, he continues to record the process unfolding within his own psyche, which is reflective of the events in the larger collective. He continues the process until near the War's end, and then spends more than a decade devotedly elaborating, amplifying and illustrating the material that burst upon him during that time in order to render it comprehensible.

The Red Book is not "personal" as we use that word now. It is "personal" in the sense that it details one individual's very unique experience of coming into relationship with what Jung termed the Self, and in prior times was referred to as God, but it is at the same time very impersonal, and actually universal, in cataloguing the drama inherent in any person's formation of that relationship. The book is at home with The Odyssey, The Divine Comedy, Goethe's Faust, and, as much as anything, The Red Book is Jung's response to Thus Spoke Zarathustra and to Nietzsche's proposition that for modern man, God is dead. The response is that God is neither dead nor to be found in outer religious, national or political containers, but is to be discovered and struggled with in the living of each individual life.

A not uncommon dream is of stumbling upon a previously unknown addition or wing of one's dwelling, which addition is found to be many, many times the size of the existing structure, and to contain objects and treasures of previously unimaginable value, interest and numinousity. One is filled with awe and wonder at the new found wealth and possibilities. The experience of encountering The Red Book after spending 30 years in Jung's existing body of work is equally stupefying. That there could be so much more that Jung had to share and communicate about the human soul seems not just improbable, but impossible. Yet The Red Book is that much, much larger, more nuanced and tremendously numinous structure that is behind, under, around and the foundation for all of Jung's subsequent ideas, theories, publications and works. Extraordinary.

Truly incredible!

By N. Furlotti

I HAVE the Red Book and am in the process of reading it. It is beyond description! This truly unique book represents the personal journal one courageous man took into the dangerous realm of the unconscious in search of an understanding of himself and the structure of the human personality in general. In the process, Jung regained his soul which was lost in the contemporary malaise of spiritual alienation. Liber Novus, as the book is called, represents a prototype of the individuation process, which is seen as the universal form of individual development. Jung was a psychiatrist who worked with schizophrenics. He intuited that their fantasies held meaning important for their healing and saw that some of the fantasies corresponded to mythological motifs. This curiosity lead Jung to his own decision to drop beneath consciousness to explore the realm of these fantasies, the realm of the "dead". He did this without chemicals or inducers but through a process he called active imagination. An inner world opened up to him to explore, which he documented in his writings and paintings. The book itself is like a medieval manuscript created with great care. He worked on the book for 16 years, giving it to others to read and edit with the intention of it one day being published. Liber Novus is a book of wisdom and deserves to be studied. It invites the reader into the world of imagination--like the dream world. I have studied my dreams for years and the language is similar. It shows what we have to learn when we slow down and listen to the inner voices. I thank Jung for giving me a guide to the soul, or human personality--which ever language one prefers.

elaborate journaling

By Slainte

This is a fabulous example of publishing. That's the price of the book. Beautifully bound and presented, the paper stock is of the highest quality. Though a lot of what one finds in the Red Book has already been published, Liber Novus proper seems to be the Jungian bible or the completion of it - Memories, Dreams and Reflections being the other part. When compared with the likes of William Blake's illuminated writings one gets the impression that something along these lines was perhaps what Jung was attempting - Liber Novus being a simplistic example, but it is perhaps unfair to make such a comparison with the unique imaginative 'intelligence' and artisitic expression of Blake. The Red Book seems to be little more than a convoluted dissolution of the Judeo-Christian mythos by means of creative visualisation. To sum up, the Biblical inheritance in the dialogues and visualisations presented in the Red Book is sublated by Jung's new gospel of 'confronting' the 'unconscious'. Reading the Red Book is like reading a disjointed fantasy novel expressed in poetic prose - fantasy not in the sense in which J.R.R. Tolkien spoke of it, but mixing in this and that element from the mundane to the mythical without regard to any cultural or historical context to make a point and thus underminding the objective integrity of such elements. Dr Jung liberally lifts biblical quotes out of context and places them within an edifice utterly antagonitistic to their authentic (their original) meaning - this sort of disingeuousness characterises the Red Book. The Red Book is the crystallization of the tendency of Jung and his followers to present his internal and external life as objectively extraordinary or uniquely wonderful, as containing an objective truth that must be generally applied as a template of self understanding for those who were not Carl Jung. After having read the Red Book, I would concur with those who have said that the 'unconscious' which Jung 'confronted' was in no way 'collective' but simply Jung's own in a Freudian sense.

P.S. The responses in many reviews to the visuals of the journal are surprising. To make any favourable comparison of the effort in this publication to the Book of Kells or any other such illuminative work is indication of the lack of exposure of some of the readers of the Red Book to culture and history in general - especially that aspect of visual culture which Jung was trying to replicate and implement for his own purposes - I can recommend "Illuminated Manuscripts and Their Makers" by Rowan Watson for those who are interested in expanding their knowledge with regards to the efforts exhibited in the Red Book. I can also recommend the works of Richard Noll (Jung Cult and Aryan Christ) as a further means of getting a clear grasp of the kaleidoscope of Jung's world view which the Red Book is. How many who have the Red Book will read it? Like the calligraphy and artwork, the narrative is laboured and works hard to be mystical, is disjointed as it was edited together by Jung from writings which did not necessarily share the same page when he originally penned them and is steeped in grandiose language. It is not, for this reviewer, a rewarding read. By the time one concludes Jung's 'Scrutinies' and the following commentary by the editor, it has been a tedious journey wading through a product that is so heavily the exhibition of the mind-in-his-time-and-place of Jung as to be of only fanatical interest. It is generally accepted as Jung's presentation of his journey to individuation - achieving a conscious relationship with a regenerative intelligence that is not confined to one's native socio-historical context. Keeping this in mind, consider the following:

In a 1933 interview on Berlin Radio (this at the time that his former mentor Freud had been banned and his books burned) Jung remarked:

As Hitler said recently, the Fuhrer [sic] must be able to be alone and must have the courage to go his own way. But if he doesn't know himself, how is he to lead others? That is why the true leader is always one who has the courage to be himself, and can look not only others in the eye but above all himself.

In Jung's 1934 paper The State of Psychotherapy Today he wrote:

Freud did not understand the Germanic psyche any more than did his Germanic followers. Has the formidable phenomenon of National Socialism, on which the whole world gazes with astonishment, taught them better? Where was that unparalleled tension and energy while as yet no National Socialism existed? Deep in the Germanic psyche, in a pit that is anything but a garbage-bin of unrealizable infantile wishes and unresolved family resentments...The 'Aryan' unconscious has a higher potential than the Jewish...The Jew who is something of a nomad has never yet created a cultural form of his own and as far as we can see never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development...The Jews have this peculiarity with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary.

When Dr Jung expressed these views he was nearing 60 and had had the better part of two decades in which to allow the main of his `confrontation' to mature and bear fruit. If these are an example of the `good fruit' of individuation it certainly gives one pause. Timeless, wonderful? Dr Jung is very much a man of his time and his unwieldly journal seems to be more accurately an exposition of the very `bin of unrealizable infantile wishes and unresolved family resentments' which he described in his 1934 essay.

Apart from the publishing quality the content doesn't reward one for the cost and burden (size, weight, where to store it) of the final product - the mythologised extraordinary and mystical volume of Jung confronting his posited `collective unconscious'. Had this work been published as a modest yet respectable glossy art text it would read as it is - an interesting example of psychoanalytic journaling that includes unaccomplished artwork accompanied by an exegesis by the editor. Jung was a replicator. The Red Book is evidence of this - alchemy, myth, mandalas, symbolic motifs, ideas contemporary in his Theosophical climate about prophecy and spirituality. If one wants a glamorous publication for the coffee table it might be worth the hundred pounds. Many interested in Jung expect that the path to individuation has something to do with reaching truth - yet if my experience of it is any gauge it's simply one of a thousand means of distracting oneself from that which one pretends to - truth. If the Red Book is the testament of the Individuated, having read the Red Book one might argue that Individuation is nothing more than an unmentored version of one struggling towards the grade of neophyte in any Western mystery school (though bereft of Jewish mystical frameworks). Apart from the mention of some dreams presented as precognitive (for those with experience in sharing dreams one learns that this is very common and so can be set aside as a recommendation for the importance of Jung's narrative) the Red Book is largely fantasizing. Reading, I considered whether the narrative is engendering in its author authenticity - the truth of oneself, one's place in life and history, including a posited non-rational meta-meaning that is more than developing a hyperbolic view of oneself by means of imagination. The Red Book is, as stated in the main review, a journal, one that took him decades to compile, based on other diaries and notebooks, and to bring to the sort of the completion that the facsimiles give evidence of. As such it is as it seems - a personal labour and the artwork is laboured as is the calligraphy whether or not he intended his exhibition for his eyes only or a 'select' few. This is journaling as a craft, yet when compared with the insights presented in the journals of so many other 'names' of history one could argue its fuel for fame will be with regards to how big it is (mimicking the large parish bible, perhaps). If anyone reading this has ever seen an example of the beauty of Tolkien's handwriting in an ordinary letter to his publisher and makes any comparison with Jung's calligraphy it becomes clear that the real interest with regards to visual aspects of the Red Book is the exercise of it rather than the results. In an attempt to contextualise the narrative of the Red Book some biographical awareness of its author is essential. Since the Enlightenment our society has been heading with increasing momentum towards irreligiosity - a totalitarian secularism. At the turn of the century those recognising the human need for the religious-like found a like mind in Jung the psychoanalyst (it is important to make the distinction between Jung's taste for the religious-like as opposed to religion proper since he despised traditional/organised religion). In order to consolidate a viable `disorganised' (relativistic) religion he posited a `collective unconscious' that is something like the `treasure house of images' of the ninth kabbalistic sephira. In order to make a viable psychoanalytic study of this he needed proof. Again, a little awareness of the facts surrounding this exposes Jung as something a charlatan - his collective unconscious is no more based on empirical evidence than the ascended masters of Mme. Blavatsky's doctrine - so the `experiences' related in the Red Book remain idiosyncratic and offer no `great' narrative. It is difficult to disagree with early Freudians that after his break with Freud he began to exhibit a narcissism bolstered by his place of privilege in society - a society (most especially in a professional sense) from which he steadily withdrew to the degree to which his worldview began to be subjected to its rigour - scientific and otherwise. While he removed his work from confrontation with professional rigour he kept himself very much in the distractions of the world in a contemporary 'epicurean' sense which, as anyone with even a vague understanding of mysticism knows, is antagonistic to the mystical process - the understanding that a Carmelite must gain with regards to the confrontation with the desolate wasteland of the stripped 'self' that Dr Jung pretends to is perhaps a helpful way of contextualising his creative fantasy for what it is. The impression given in the narrative of the Red Book is of a man describing himself as the prophet of a new psycho-secular religion and he the Christ of that religion, his 'sacrifice' of the 'confrontation' opening to the world a new psychic truth. In this he joins the ranks of a long line of self-proclaimed 'Christs' of various ilks. The Red Book is supposed to be the bedrock of Jung's system of Psychoanalysis. Jungian Analysis has been proved to be short on its healing capacity (especially in comparison to contemporary Freudian Analysis according a recent extensive study in Sweden - see Lisa Appignanesi's account of psychoanalysis). As such 'Jungian analysis' remains in the sphere of the 'mystical' as Karen Horney categorised it. Mystical psychology's focus is 'redemption' in a psychological sense although most contemporary psychologies (professional) seem to be rejecting this as a legitimate arena in analysis, though one might choose to apply the 'mystical' method of active imagination after the manner of Jung's journal in order to achieve a psychological regeneration under the guise of bringing the posited unconscious and conscious into dialogue in order to live the 'transcendent function'. Based on the Red Book one could conclude that there is nothing at all mystical in either the Jungian process or results - they remain visualisation pursuits that reject the 'beatific vision' of the authentic mystic and, instead, seek to encourage a sort of narcissistic idolatry - a constant staring at the imagined, and inflated, 'self', depending on the narcissistic tendencies of the individual employing them. Jung was determined to the last that his way was a science on the one hand and he also claimed the Red Book meditations as the storehouse and wellspring of all his later work. His exploration in the Red Book is constantly towards the religious and philosophical - religious personages, religious quotations, and the magico-religious yet all that happens through the inclusion of these elements is the positing of the myth of the self deification of the 'hyper individual'. A recent book by Marcus Pound titled, 'Theology, Psychoanalysis and Trauma' has been called 'the most important sustained reflection on the relation of Theology (the study of religion) and Psychoanalysis (Jung's 'discipline') to date'. One would think this the perfect place to investigate the legacy of Jung who worked to marry the two, it would seem, throughout his career. However, Freud appears, Lacan, Kierkegaard, but it is significant that the psychoanalysis of Dr Jung and his contribution, whatever it might have been, is completely absent. Looking at the Red Book with a critical eye the suturing and appropriation of certain biblical texts and people and texts and personalities of the Church (even the mention of the author of the Imitation of Christ, for example) comes to appear mischievous at best given that he was known by his disciples to have, as stated earlier, despised organised religion which he saw as antagonistic to this sought after 'self'; as such his appropriation of such texts seems disingenuous since his purpose for employing them is at odds with their reason for existing in the first place; the point being that Dr Jung's narrative lacks integrity because it denies the integrity of that which pre-existed it (as far as the narrative of the Red Book is concerned) which is made clear in the way the Red Book cuts and pastes the fruits of the mystical and religious past with a disregard for that past as if it had no history but was itself nothing but a sudden penned imagining like his own. While many saw Dr Jung as something of a champion of the religious and the irrational impulse under an increasingly materialistic hegemony his Red Book is a testament of his acquiescence to this hegemony by positing his 'religion of one' - much like the theoretical 'audience of one' posited in contemporary media studies, which is, ultimately, antireligious since religion is always shared (it is not a 'circle of 'I'') and posits an absolute as opposed to the horizontal relativism of the `religion of one'. Jung's 'synthesis' does not hold together at any point which is why it is constantly degenerating into weaker strains of the same narrative commitment to the 'hyper-self' employing biblical and mythical masks to keep the essentially one dimensional characters of the Red Book narrative `clothed'. This fragmented religion of the hyperbolised self is at odds with any sort of worthwhile understanding of real relationship, either in a religious context, or merely a secular one. It is perhaps for this reason that, in a period of time when Dr Jung was consolidating his method based on his inward search (imagined dialectic), there were many of his contemporaries who simply had a keen political awareness or a well developed conscience who were able to discern the evil in National Socialism, while Dr Jung appears to have missed it. At best the Red Book might spark an interest in the texts and personages he has appropriated. In pursuing those primary texts and investigating those persons appropriated in their original context, the reader will find genuine 'confrontations' from which there is something authentic to be learned. Jung maintained that his way was a science and that that science was based on the discoveries exhibited in the Red Book. With regards to Jung's 'science', why such an idiosyncratic `science' has survived a century (or though in an ever thinning manner) rests on possibly two main reasons - one being because of the matter it deals in - tradition (folk, mythic, cultural) and their expression in dreams, imaginative exercises, and serendipity which he renamed `synchronicity'. The other being because the process is essentially narcissistic. With regards to the first, these things are amalgamated in religious tradition. Religious tradition included what we knew of `science' for centuries. Science had been funded, pursued and expounded through Church agencies and members for several hundred years before, as a result of the Reformation, science no longer needed the Church as a patron; the dog turned around and bit its master with a vengeance, only to find itself with a new patron - Secularism. The secularised political mind brought a slew of miserable projections into experience (Jung wrongly placed the `misery' label on Christianity as a specific charge). To the inheritors of the Enlightenment Moses and Jesus Christ were pseudo-history and Judaism and Christianity labelled an infantile neurosis. The religious-like, therefore, found its place in an increasingly irreligious era. In 1909 President Eliot of the Harvard Divinity School gave an address in which he saw the doctor and 'sanitary inspector' as replacing the priest and the bishop as 'bearers and representatives of a new order'. Jung was one of an entire generation of upper class well educated men of the period who saw themselves as secular priests, or gurus. The `way' presented in the Red Book does not address the meaning or lack thereof of a person's life, both internal and external in any truthful way, as self directed fantasy that need not test itself against anything but itself within the confines of its own mental domesticity, no matter how distracting, never could. Jung's `logismoi' (torrent of thoughts) written up in the Red Book never become the `nous' of the mystic which is the `eye of the heart'. An awareness of the reality of a Carmelite nun living with the restriction and rigour of the cloister without the relief of distraction from true confrontation with the wasteland revealed by the self undergoing kenosis in the quest for the `eye of the heart' is the surest way of, through comparison, understanding Dr Jung and his 'confrontation' as being confined to creative fantasy. This leads directly to the second possible reason for the popularity of Jungian practices - their essentially narcissistic application. So, it is perhaps, at least, in part, for the above reasons that contemporary seekers are still to some degree, under the spell of Jung whose teachings have impressed upon the post-Freudian-1st-world-imagination a narrative of muddled libertarian and egalitarian (the text cannot distinguish between the two) imperatives and Wagnerian grandiosity of fanciful narcissism. The exhibition of the hyperbolised self in the Red Book makes one all the more aware that our society seems militaristically narcissistic. It is this loud beat that our society, and usually ourselves, however much we fancy ourselves as standing outside such mediocrity, appear to be marching to. It is interesting that Martin Freud's memory of Jung was that he seemed more like a `soldier' than a man of science. Moving beyond Jung, surely one of the most important contributions to psychoanalysis of the 20th century is Viktor Frankl's. As one commentator wrote of Frankl, he was a teacher whose learning and wisdom is based on `experiences too deep for deception'. The `experiences' written about in the Red Book remain fantasy by comparison. One of the real tests of truth is its ability to stand rigour, to stand testing and tempting. As a science Jung is little used, if at all, in contemporary psychiatry, he is more prolific in magical schemas and the like, or as a means of critical theory but only in its 'post' application. To what rigour has Jung and his contribution been subjected? Richard Noll - here we see the author of the Red Book as a former student of Freud who subsequently immersed himself in a very insular world of idiosyncratic theosophy. When you first take the Red Book out of the packaging it has impact, like the Indiana Jones like ads presenting the scanning of the pages that are on the Internet; it is huge, it's bright red, it is a product of rare publishing quality in contemporary publishing. Consider what you paid all that money for, what has been mythologized for decades - a journal of laboured artwork and calligraphy replicating theosophical and alchemical concepts in a 'modern' narrative of occult pathworking influenced by Freudian analysis employing a process of argument between the characters of thesis-antithesis-'synthesis'. 'Synthesis' in quotes because Jung's presentation of the third given or transcendent function is as often a depressive sense of meaninglessness as some sort of accomplishment, only quickly to be re-masked and subjected to another tangent of 1-2-3. In this way the depressive synthesis is never actually faced in the sense that, say, the earlier mentioned Carmelite must do without being able to shrink back into the distraction of Jung's system of internal pseudo-dialectic (there's no actual argument or discussion between persons here, only ideas of himself), the aim being to validate Jung's sense of 'authenticity' based on his fantasy of himself and his 'dialectic' ensemble. I gave the fabled Red Book two stars because for me, it seems to have more to do with the emperor's new clothes than the seeking after truth or the worthwhile foundations of an applicable and effective psychoanalysis.

Believe the hype? Reading through the reviews and comments it seems few if any of the readers of the Red Book know what they are reading. Dr Jung's Red Book reveals a fetishist - in the Marxist sense. His fetish being his idea of himself. His self is seen narcissistically through a rehashing of the great narratives of monotheism, pantheism, capitalism, and magic retrojected back upon the idol of himself - fetishism; the hidden name of his Philemon might be libido dominandi. This is 'modern' narcissism - simple, unremarkable, no matter how much glamour is used to put the glitz on it. His gnosticism has more to do with Marx's definition than the 'gnostic' who was called a heretic in the first centuries. His contribution is along the lines of the forgotten Ozymandias' - 'look upon my works ye mighty and despair'. The text violates history and the reality of religious tradition without rest - the text, in short, is a long fantasy of violence against the integrity of the aforementioned; a pretend 'Aristotelian' poiesis that revels in a retrojected protean self the final aim of which is apotheosis - not by elevating anything but by debasing everything and bending all to the lodestone of one's 'active imagination'. It is the anticipation of the virtual - shadow of the real - this virtuality appeals to the totally commoditised Westerner with little understanding of simulacra the desire for which is antagonistic to the desire for truth - truth requires that one 'recant and relent' in the face of Truth - but 'true' to narcissistic form this 'myth' demands that all becomes manipulable nominalism, able to be edited rehashed and remashed to 'suit' oneSelf - it is straightforward Prometheanism that seeks to forget the burden of the real in the quest for a posited divine (fantasised) self/individuated self. There is no authentic engagement with the theology and metaphysics appropriated in the RB - his religion is a mimic that doesn't want to recognise the nature of its desires or the instigator of its fantasies - the processes presented in the RB have one real aim - to engage in a sustained 'forgetting' with regards to truth, God, conscience and especially authentic self-examination - the 'folksoul' angle is as detraditionalised and relativistic as all the RB devotions and need not make a commitment to anything other than its own perpetually current fantasised mastership. This belongs to the new age proper - that network of ideologies that have not the slightest interest in integrity or history only appropriating whatever the mind can get its 'hands' on to perpetuate the delusion of self-deification. This is the pseudo-metaphysics of postmetaphysical discourse. In the RB religion is rhetoric - it is the imaginative interaction or simulation of the religious-like that leaves one free to never bend the knee or experience transformative and soul maturing humility through the actual prophetic and shared tradition of open mystery - in other words the reality of religion is avoided in the name of the self-suited - the RB 'experience' has more to do with the 'experiences' to be had via x-box and the like than that transformation to be undergone through engaging with Logos that will make of the mind a slave to the heart and of the heart a devoted slave to the ineffable Divine which the 'service' of the self or the 'gods'(protean 'selves') avoids in an endless narrative of displacement. This presents a self-determined artificialising of the 'self' in the name of bending nominalised truth to the socio-historic and passing individual. This sort of individual dismembers and (tries to) murder God-given personhood for the sake of the rheotric of individuality. Basically placing a pretender on the throne - the nefesh behamit 'displacing' the Nefesh Elokit.

p.s. 'Recant and relent' is a reference to the Book of Job - another historical religious text which the non-theologian Jung felt himself qualified to 'secularise'.

Alexis

You seem to have an affinity for:

'....the common habit of explaining something unknown by reducing it to something apparently known and thereby devaluing it. The phrase is borrowed from William James, Pragmatism (1907) p 16: What is higher is explained by what is lower and treated for ever as a case of `nothing but' nothing but something else of a quite inferior sort'

PS: Some of Richard Noll's assertions, when cross referenced, have been invalidated.

Slainte says

The burden of mystery is understanding that one can never know and knowing that one can never understand that upon which one relies for one's very existence. This burden of trust is only the beginning of experiencing the mystery and it is a mystery shared in authentic community - 'gnôthi seauton' was not carved into the stone above a private sanctuary for the few of the few by the few - the modern equivalent of the Delphic temple would have to be St Peter's Basilica. The Red Book 'confrontation' narrates no 'consistency of selfhood' it is not interested in the 'higher' or the 'unknown' - it is only interested in dismissing these through an imaginal arrogation of its own projection of the 'higher' and the 'unknown'. Does anyone know if Jung ever practiced fasting in his life? When the physcial comforts and sustenances are gone or suspended one learns very quickly what is left that is real to hold on to. Since he alludes to a symbiosis with historical personages who understood the fast (Jesus of Nazareth, Thomas of Kemp), it's a valid question to put with regards to the 'mystic' Jung. Why readers cannot see that a non-Christian sublating the sacrifice of Christ, and a non-ascetic declaring affinity with the likes of Thomas of kemp, and someone unsympathetic to the concept of Judaism appropriating the figure of a Jewish prophet in what is essentially an abrogation of the aforementioned is not simply a work of idiosyncratic uselessness is odd. Let's say we want to heal ourselves with some sort of alchemical tincture or stone, yet we ignore the objective tradition of spagyrics, and pick and mix this and that herb without a wit of consideration for their traditional application and their alchemical worth, ignoring measures, weights and process and all the discipline that goes into such an endeavour because after all its only worth is fantastic. For the author of the RB none of his appropriated treasures have any objective integrity thus allowing any individual to rule over everything prior to themselves as long as they give more 'weight' to their self-induced fantasy than to any objective data. His appropriation of the path of `theosis' (an unfortunate and misleading term, `sanctification' being much more helpful) is in keeping with western esotericism that envies the `throne of god'. The real (that with objective integrity) path of `theosis/sanctification' involves humility not hubris, asceticism not `Epicureanism', and communion with the mysteries of the God become human.

BTW - would be interested to know which cross referenced assertions from which Richard Noll book/s have been invalidated. He wrote prior to the launch of the RB and so, when making reference to the RB, kept his focus only on what actually was known while writing. His works, however, at least to this reader, are about informing his readers as to the ideological, social and historical context into which Jung was born and, from that grounding, presenting biographical evidences of Jung's response to that mileu. Even though his books were published many years ago, the overview of his subject is in no way undermined by the launch of the RB - quite the opposite. I hadn't read Noll until I had 'consumed' the RB. I was somewhat incredulous at Jung's journal 'this can't be what all the fuss is about?' Applying even a modicom of historical, theological, psychological and the visual arts rigour to the journal and swiftly, at least for this reader, the hype is exposed for what it is. If we want to gain a greater understanding of the vacuous, instant, yes, narcissitic psuedo-spiritualities of the new age and contemporary thin religion, Dr Jung's 'journey' is a useful mirror for seeing just how this sort of 'sacrifice' of personhood for a fantasised individuality/self fufilment/empowerment (and all that) is successfully sold - but beyond that there simply is no beyond in the Red Book or in the flimsy do it yourself instant 'religion' and 'spirituality' of 'wish-fulfilment tucked away in some private "ineffable" realm'.

C. Hurwitz says:

An interesting question. Does the fact that Jung made these and other anti-Semitic comments during the Nazi period invalidate his work?

Slainte says:

Good question to be considered by those who do suppose that his work has a valid contribution to the progression of one's understanding of oneself - that is in finding the consistent self - I would suggest that his approach achieves quite the opposite. One must decide for oneself, based on his personal journey evidenced in his red book and scrutinies (these being the scripture of Jung's way), whether or not he achieved anything that one would want to follow after. What I see (as mentioned in all above comments) is a narrative of arrogation, abrogation and appropriation the only consistency in which is the denial of objective integrity with regards to all the varied matter he uses to dialogue internally in order to find the authentic voice - almost as if nothing apart one's view of oneself is real - which is a wee bit erring too far towards a clinical definition of madness (he certainly took to heart the portrait of a genius put forth by Schopenhauer and while there may be a germ of truth in Schopenhauer's thesis would anyone call Jung a genius? Without the genius of Freud would Jung exist in popular consciousness? Genius' stand against the grain of the time, creates the wave that builds to a crest etc. Jung was one of many followers of the time, spinning the rhetoric of the time according to their psychological peccadillos. A good publicity machine does not equal genius. Surely his mirror gazing was in no small part is why Dr Jung failed to see the evils he was initially lauding in National Socialism (either this or there remains the possibility that he understood all too well National Socialism and simply distanced himself when it's popularity disappeared with the moral outcry from the rest of the world). The issue is surely efficacy. Jung's followers, and Jung himself made great claims with regards to their superior rank as 'analysed' humans, that it made them elite, more aware, more authentic, achieiving a kind of philosophical theosis. Would someone of such unique awareness and authenticity be so able to see the world around them with such a profound lack of awareness? If he had say developed the vaccine for polio, then we might consider that such a beneficial contribution offsets such damaging Antisemitisms and misogynies. Therefore, yes it does matter that Jung, a new age guru, was fond of National Socialism and that he thought himself, by 'virtue' of his 'Germaness', maleness and standing in society, better than Jews and women - it matters because many Jungian's and Jung himself make claims to being elite human beings - people who have actively imagined (analysed) away the dross to become human gold. If in fact Jungain processes simply bring one to the point of being so convinced of one's goldness so that one no longer understands how much a standard, confused product of one's milieu one is, then what is the worth? If Jungian processes did not rescuse Jung from his smallness and caged historicity, why should it rescue others?

C. Hurwitz says:

Exactly. There's a big difference between someone like Wagner, who was an anti-Semite and Jung. Music has nothing to do with what type of person you are or your philosophy of life. Analysis on the other hand is supposed to make you better understand yourself and your place in the world. I submit then that if the result of all his work and theorizing is support of Nazism, his whole body of work becomes invalid.

The Dark Knight says:

Someone took a little too much Philosophy in finishing school, hmm? You must be a riot at dinner parties. Why don't you try writing your next scathing review in comprehensible English so that the rest of us can actually engage with your points.

Slainte says:

The red book is written in a laboured style is not a light read; the language, as I mentioned in my review, is grandiose and full of jargon. The comments above shouldn't confound anyone who has 'understood' the red book. One dissenting voice perhaps shouldn't inspire such disappointment in readers who are happy with their red book purchase.

E. Johnson says:

"Reading the Red Book is like reading a disjointed fantasy novel expressed in poetic prose - fantasy not in the sense in which J.R.R. Tolkien spoke of it, but mixing in this and that element from the mundane to the mythical without regard to any cultural or historical context to make a point and thus underminding the objective integrity of such elements."

You go on to list the Bible as an example of something he writes without context. I tend to find this a horrible example as the Bible is so vast and is not only a historical book but for many a spiritual book. Jung wrote spiritually. He wasn't writing a critique of the Bible so such context isn't needed. I agree that this is a lot like journaling. And to Jung this led to many of his ideas that have been the foundation of a major leg of modern psychology. So why wouldn't people be interested? But that doesn't mean that it should be read as critical fiction or in whatever strange academic box you're trying to put it.

If your real beef with Jung is quotes he made about Jewish people, then say so and save us the dull diatribe.

WRainer says:

Debunking Jung is like a rocking chair, it moves a lot, but gets you nowhere.

I wonder before whom like to prostrate yourself, or as you put it, choose to 'bend your knee', before which chartered religion? Mind you they too are mediated through human beings, subjugated through cults, run by a rabbi or pope or guru of whichever kind. So, Jung, for a few shillings a week taught his clients how to be their own guru who needs no mediator, this being a universal function, available to anyone, that is, the ' transcendant function', in Jung's terms.

Your animosity, erudite to be sure, sounds to me like sound and fury, signifying nothing (exactly that which you accuse Jung of!)

Gehen Sie in sich, alter Mann!

Indeed, Richard Noll used to be a Jungian disciple too, until they didn't accept him for training at an C.G.Jung-Institute in the USA. Check out Noll's papertrail and you will see that he always wanted to be topdog (see his publications as a cultural anthropologist), on witchcraft, magic, werewolves, etc. Noll's practice of quoting out of context is despicable! But, I guess, tear down your erstwhile idol - which may be a necessity, if you've overdone it!

I think you've got it wrong, Jung did just what you accuse him of, he stopped working on the Red Book, and developed his psychology further through detailed studies of alchemical texts. The results of that work are the several volumes on alchemy as a psychological system of transformation, contained in Jung's CW (Collected Works)

Frankly, I wonder why you continue to kick a dead dog?

On Noll: why don't check out Noll's writings in Jungian Journals before his 'break' with Jung? He used to run a Jungian group in Philadelphia, a group which he referred to as his Jungian mystic circle. Noll, another Saul turned into Paul.

I wonder what is the biographical basis for your rage at Jung?

I think you don't give Jung's academic/professional achievements his due. Jung had an excellent reputation (the Zurich school, Bleuler, Jung, etc. already in his own right, especially his studies on Word Assocations remains a mile stone in experimental psychology as well as his initial work on psychological types.

Also, as long as Jung championed Freud (especially his sexual theory), he was good enough to be placed on a pedestal by the Vienna circle.

As for Freud's claim to genius, how about his being dead wrong about the function of cocain in eye surgery? Or, Freud's falling totally under the influence of Fliess with his tick for finding numerical rhythms in the lives of his patients, and incidentally, Freud's assisting in the operation of women on their noses, for supposedly displaced sexual yearnings (see Jeffrey Mason, The Assault on Truth). Now there is real genius for you, I suppose?

O Dear, now Hurwitz has joined Slainte, what a wonderful accusatory duo. So, Jung didn't like what the Jewish analytic establishment was spreading the world over, with Freud himself, instigating it all amongst his lesser brethren. Just read Freud's letters to his be-ringed inner circle, next to each other. Freud certainly knew how to dish it out about each one to the other, behind their back! Divide and conquer, seems to have been the operating principle.

Perhaps the youthful, irreverent Bob Dylan said it pithily: Don't follow leaders, watch the parking meters! (Their time is always up, too soon?)

wdp.rainer@gmail.com

E. Smyth says:

Slainte, while I find much of your review interesting (a well-considered, well-written contrarian view is always interesting) and much of it valid, I must take issue with your assertion that people who adore Jung's paintings and compare them to Blake and the Book of Kells *must* be dilettantes with no real solid background in the arts.

This is grossly unfair and I suspect self-serving at bottom.

As for me, my aesthetic credentials are pretty unassailable, having attended two of America's top art fine art schools (one leaning towards conceptualism, the other towards traditional academic practices) and worked successfully as a professional artist ever since. I also tend to know more about art history than the average fine artist, having made a point to study it in depth (I also have a second major in history proper).

I say all that not to boast but in preface to a defense of those who feel deeply moved by Jung's paintings. Having seen all of the Red Book and paid especial attention to the illustrations, I see no reason to insult either Jung's illuminations or his admirers. His work is highly aesthetic and sometimes quite beautiful. It is also rather forward looking, anticipating both the psychedelic style of the 1960s and the exceptionally graphic look of the 1980s (especially his approach to abstracted human figures).

Jung's paintings may not be your cup of tea, Slainte, but the fact that it appeals to some does not in itself indicate ignorance or lack of sophistication on their part. Indeed, your remarks on that score say an awful lot more about you than it does about them.

And don't forget Freud's deliberate mendacity in placating the Victorian outcry around him by abandoning his early assertions of the role of incest in creating hysterical paralysis in women, and then fashioning such nonsense as penis envy and the Electra complex in its stead, so as to "blame the victim" (as we say today).

Încă din anii copilăriei, într-un anume punct despre care va păstra toată viaţa o vie amintire, C.G. Jung a sesizat că în el sînt două persoane diferite, trăind în epoci diferite: copilul fragil şi temător al prezentului său (Unul) şi bărbatul autoritar, puternic, influent (Altul). Primul era „suma emoţiilor trăite“, Altul era figura atemporală, nepieritoare; Unul era fiul familiei Jung, mai puţin inteligent, atent, cuminte, silitor şi curat decît alţi copii, Altul era bătrînul sceptic, neîncrezător, departe de lumea omenească, dar apropiat de natură, de soare, de lună, de creaturile pline de viaţă ale nopţii şi viselor şi de toate evocările nemijlocite ale lui Dumnezeu. În viaţa lui Jung, Altul – figura interioară, sau Numărul 2, cum obişnuia să-l numească – este subiectul autenticei sale autobiografii, este specificul vieţii lui, Cartea Roşie fiind rezultatul explorării cu multă seriozitate a „Marii Întîlniri“ cu acest Altul, cu Sufletul în diversele lui ipostaze.

Simţul special pentru Altul a

funcţionat şi în raport cu ceilalţi oameni, la început

în raport cu mama lui, pe care o auzea, în anumite

situaţii, vorbind cu vocea ei numărul 2, o voce venită din

depărtări, de parcă un spirit atemporal, o anume divinitate se

cuibărise în ea. Descoperirea unui spaţiu aparte prin care se

mişcau oamenii dubli, oamenii vorbind pe două voci, îl

copleşeşte de certitudini despre care ar fi vrut să vorbească, pe

care ar fi vrut să le împărtăşească celor mulţi, dar era

privit cu suspiciune, uimire şi teamă. Jung a învăţat

destul de repede că în societate nu poţi vorbi decît

despre lucruri „cunoscute“ de toţi; dacă îţi permiţi

să-i jigneşti pe oameni vorbindu-le despre lucruri cu caracter

excepţional – rezultate din revelaţie, vis, viziune etc. –, te

paşte, în mod inevitabil, pedeapsa. Această pedeapsă este

singurătatea şi izolarea.

Viaţa lui Jung, privită din această

perspectivă, nu a devenit excepţională pe parcurs, ci a fost aşa

din momentul în care povestea lui a început, din acel

punct în care a auzit pentru prima oară vocea Arrhetonului –

„oaspetele străin care venea şi de Sus, şi de Jos“ (Amintiri,

vise, reflecţii, p. 34). Dar oare cine era acest Spirit? Oare cine

era această inteligenţă superioară care vorbea în el? –

iată frămîntări care începuseră deja în anii

fragedei copilării şi care au decis începutul, inconştient,

al vieţii lui spirituale: „Lumea copilăriei mele, în care

tocmai mă cufundasem, era veşnică, iar eu fusesem rupt de ea şi

mă prăbuşisem într-un timp ce se derula fără oprire,

îndepărtîndu-se din ce în ce mai mult. Trebuia să

părăsesc cu forţa acest loc, pentru a nu-mi pierde viitorul“

(Amintiri, vise, reflecţii, p. 40). Jung a avut în acel moment

revelaţia „caracterului de eternitate“ al copilăriei lui şi a

ştiut, instinctiv, că în viaţa cuiva contează numai acele

situaţii şi experienţe în care lumea „nepieritoare“

pătrunde în orizontul limitat şi trecător al existenţei

personale, în durata ei.

Golemul – un arhetip al Sinelui

În acei ani s-a întîmplat

un fapt care se va dovedi de o importanţă capitală pentru viaţa

lui Jung şi asupra căruia atenţia biografilor nu s-a fixat: la

vîrsta de 10 ani, cînd simţea foarte acut scindarea

interioară şi era foarte nesigur, s-a simţit condus de o forţă

inconştientă şi a început să cioplească linealul pe care-l

avea în penar, dîndu-i forma unui „omuleţ“ pe care

apoi l-a decupat şi l-a colorat cu cerneală neagră, i-a făcut un

culcuş şi i-a găsit o bună ascunzătoare în podul casei. În

timp, i-a dat omuleţului în păstrare o sumedenie de secrete,

scrise pe hîrtii care ajunseseră să formeze biblioteca acelui

omuleţ. Jung scrie că, procedînd aşa, i-a dispărut

sentimentul chinuitor al dezbinării pe care o simţea în

interior. El consideră acest moment ca fiind ieşirea lui din

copilărie, un moment extrem de important pentru întreaga lui

viaţă, la care simte nevoia să revină în cartea deamintiri. Nevoia de a crea un om a venit în mod inexplicabil şi

nu are legătură cu nimic din mediul lui de viaţă, în sensul

că nu a fost martor niciodată la vreo discuţie despre crearea unui

om, tatăl lui, pe care l-a interogat mai tîrziu, nu ştia

nimic despre „astfel de lucruri“ (Amintiri, vise, reflecţii, p.

43) şi nu a avut acces la o literatură pe această temă.

Cred că merită să zăbovim puţin

asupra acestui omuleţ, pentru că el este expresia unei noţiuni

centrale în viaţa şi în activitatea lui Carl Gustav

Jung, şi anume, noţiunea de Sine. Omuleţul lui Jung este un Golem,

un om creat nu de Dumnezeu, ci de către un om, o fiinţă care

primeşte suflul vieţii de la un om, printr-un impuls creator.

Golemul lui Jung – ca în romanul omonim semnat de Gustav

Meyrink – se referă la ideea divinului care sălăşluieşte în

om şi la capacitatea acestuia de a manevra propriile puteri divine,

la posibilitatea ca omul să stabilească un contact între

inima lui şi inima lui Dumnezeu, acest contact dîndu-i omului

posibilitatea să influenţeze divinitatea. În mistica hasidică

se consideră că aceasta ar fi cea mai eficientă formă de magie,

dar dincolo de acest aspect, ar trebui să reţinem că există nişte

corespondenţe, chiar o identitate între Golem şi Sine: ambele

sînt rezultatul unui act creator care imprimă o anumită

structură vitalităţii divine prezente în om. Omuleţul este

intuiţia formaţiunii psihologice pe care Jung o va denumi Sine –

o anumită imagine a lui Dumnezeu – şi el rezultă dintr-o

intenţie divină şi una omenească, fapt dovedit de coincidenţa

dintre simbolica Sinelui şi cea prin care a fost, dintotdeauna,

caracterizată divinitatea sau exprimată prin imagini (idee

dezvoltată de Jung în Răspuns lui Iov, p. 307): „Eul nu

este decît centrul cîmpului conştiinţei mele, el nu

este identic cu totalitatea psihicului meu, ci doar un complex

printre altele. Deosebesc de aceea între Eu şi Sine, în